A friend of mine recently sent me an online version of an op-ed piece that the retired NBA star Kareem Abdul-Jabar penned for Time magazine. Entitled, “Let Rachel Dolezal Be as Black as She Wants to Be,” the article is a tongue-and-cheek response to the righteous backlash the former head of the Spokane chapter of the NAACP has received for lying about her racial identity. In it, the former Lakers player engages in a thought experiment about the possibility of living a lie with regard to his towering frame as a means to make an argument about the arbitrariness of (racial) identity and the ways in which we can convince ourselves and others of our social location through the power of repetition.

“Although I’ve been claiming to be 7’2” for many decades,” he writes, “the truth is that I’m 5’8”,” adding, “Just goes to show, you tell a lie often enough and people believe you.”

Good point? Not so sure. Last time I checked, no one ever believed, nor is there a chance that anyone ever will believe, that Abdul-Jabar is 5’8”. Not to mention the identity politics of race is far more nuanced, complex, and complicated than those of height–at least in terms of the present debate.

Judging by the evidence against her—from allegations of receiving a full scholarship for Howard University’s MFA program under false pretenses to those of cultural appropriation so as to legitimate her involvement in various causes for racial justice—Ms. Dolezal has woven a masterful web of deceit around her self-identity that has allowed her to commit what amounts to a crime of cultural theft and, ultimately, an abuse of White privilege. Only recently, with the stir caused by her parents’ outing Dolezal as White, has she come under the proverbial gun of scrutiny—and rightly so.

In opposition to Dolezal’s critics, however, Abdul-Jabar, an African American by ancestry, offers a sympathetic interpretation of her situation—one that he renders through the unstable metaphor of his choice to claim himself shorter than he is. The point he is making through this dubious analogy is that race is a social construct. Therefore, if this White woman, who claims a deep-seeded commitment to the African-American struggle for existential, social and political freedom, wishes to identify as Black it is damn well her imperative to do so. This is the case, Abdul-Jabar argues, particularly in light of how much Ms. Dolezal has contributed to the Black community through her involvement with the NAACP as well as her role as instructor of African-American studies at Eastern Washington University and her chairwomanship of a police oversight commission in Spokane.

I think Abdul-Jabar is right to remind us that race is merely a social construct. Indeed, sociologists and cultural anthropologists have gone to great lengths deconstructing categories of race, gender, and sexuality, revealing to us how fluid such identity signifiers actually are. The wonderfully compelling thing about the controversy surrounding Ms. Dolezal’s act of willful appropriation is that it provides a contemporary case-study by which to reconsider fixed notions of race because of how easily it can be adopted and performed (Dolezal a prime example).

After all, as Abdul-Jabar makes clear, race is not a biological reality. It is something we inherit culturally through discourse—that is, as a matter of shared values and social practices—that is not bound to or by genetic makeup. Its only tie to biology lies in the fact that it is used as a way to classify people according to phenotype, or skin color. An historical account of race meanwhile reminds us that it is an invention of White colonialism which ushered in the slave trade and, with this, a systematic ordering of people according to a hierarchy of being predicated on prejudicial assumptions about the supposedly inferior relation of non-Whites to Whites—the latter forming the top of a social pyramid into which we, as a global society, are still locked today.

While it may be true, as Abdul-Jabar writes, that “[w]hat we use to determine race is really nothing more than some haphazard physical characteristics, cultural histories, and social conventions that distinguish one group from another,” it is also true that the cultural histories and social conventions tied up in the physical characteristics used to classify individuals according to race are imbued with a specific politics that, for people who are actually Black or non-White, carries the weight of centuries-long oppression. In light of this burden, Blackness, even if an arbitrary construct, cannot be taken up by cultural outsiders simply by dint of waking up in the morning and deciding, “I am Black.” Especially not with the same hypothetical ease with which Abdul-Jabar imagines himself as shorter than 7’2”.

Indeed, his conceit does not hold up in large part because race cannot be so easily transcended or dismissed in a society where people are still being targeted as victims of violence based on the politics of skin color. The recent terror of the #CharlestonShooting as well as the spate of historic Black church burnings offer us horrific and sobering cases-in-point.

The problem with Abdul-Jabar’s logic, furthermore, lies in the fact that he fails to account for the ways in which Ms. Dolezal has in fact overstepped the boundaries of appropriation through her spurious claim of Blackness as a matter of “identity” rather than as a “politics of identification” (see Sharma, Hip Hop Desis: South Asian Americans, Blackness, and a Global Race Consciousness, 2010: 234ff). The distinction between “identity” and “identification” here is important (more below).

By claiming Blackness as a her racial identity when she is in fact White, Ms. Dolezal has assumed a heritage of historical burden that she has never actually had to live down—despite her claims of being discriminated against (apparently, she has alleged, as the target of anti-Black and anti-White racism, which reveals further the contradictions of her past and present social locations). While it is clear, as Abdul-Jabal notes, that she has committed herself to the struggle for Black enfranchisement and has at least ostensibly aligned herself with Blackness as a kind of political ideology that signifies solidarity with the racially oppressed, her actions reveal an overt misrepresentation of the very people with whom she has taken up a co-conspiratorial relationship in the cause for justice.

Not only has she misused her White privilege in manipulating the boundaries between races through a destructive kind of border crossing, she has also perpetuated the problem of White Supremacy by abusing her privilege to claim ownership of a cultural heritage tied up in experiences of racial oppression for which the very Whiteness she has at once eschewed and taken up (to cross borders) is responsible (riffing on the insights of Beja of the White Noise Collective; see “On Rachel Dolezal, White Privilege, and White Shame,” 2015). She is, in sum, a walking contradiction of herself.

Furthermore, what she and, it seems, Abdul-Jabar, may deem an act of cross-racial association is really nothing more than a reinscription of an essentialist notion of race—the same notion she is supposedly attempting to disrupt, ironically, by donning a Black mask—that defeats her superficially altruistic purposes of taking up the Black fight for liberation.

By denying her racial identity as White and playing into a performance of Blackface that relies on a questionable appearance of phenotypic Blackness (i.e. Blackness by way of skin-type)–a Blackness fetishized in the White racial imagination (Dolezal’s to be precise)–she is enacting a politics of racial identity that capitalizes on a fetishizing conception of race which views it as a categorical difference rooted in skin color, thus associating Blackness with a kind of skin-deep essence that can be integrated as easily as picking up and putting on a facade for a theatrical display.

Despite Abdul-Jabar’s shaky comparison of Dolezal’s pitiful act to the potentially anti-racist Blackface of late entertainer Al Jolson, she deploys an identity politics that reinforces stereotypes of Blackness as a biological marker of identity and difference. She therefore seems to be at cross purposes with herself, at once reproducing (consciously or unconsciously) a racist construct of Blackness as a biological reality through Blackface at the same time that she is advocating for a more anti-essentialist conception of Blackness that informs her highly questionable commitments to the hard work of racial reconciliation.

Put another way, her masquerade of Blackness, replete with frizzy, Afro-curled hair and darkened skin tone, falls back on a White imaginary of lampooned Blackness that maintains a caricatured depiction of the racial other—an act she used to convince people on both sides of the “color line” (Du Bois 1903) of her status as a minority so as to further an ulterior agenda for professional advancement that works in irreconcilable tension with her professed value system.

Truth is, she is not a racial other and her motivations for appropriating Blackness prove dubious if not duplicitous.

With all this in mind, her act of cultural appropriation functions as a form of “othering” that decontextualizes, dehistorizes, and depoliticizes racial difference (Sharma 2010: 237) between Whites and non-Whites. She lifts Blackness out of the context, history and politics with which it is has been wedded since the dawn of the Euro-American slave trade (read: modernity) and thus silences, or reduces to invisibility, the historical realities that created Blackness as a social construct in the first place. The paradox in this is that her act of “appropriation as othering” is about both “‘love and theft’” as it “[works] through positive stereotyping, such as in the idealization or exotification of the other […]” (Sharma 2010: 240). In Dolezal’s case, it appears that her destructive engagement with appropriation happened as a matter of possessive love through thievery.

The sad thing in all of this is that she could have engaged in appropriation to the advantage of the people to whom she has purportedly dedicated her work. As race theorists recognize, appropriation is multi-directional (Sharma 2010:236); it flows back and forth across racial and cultural lines.

That being the case, appropriation does not have to be a bad thing. It depends on how one positions oneself in relation to those cultural formations with which one is associating his or herself. There are ways to engage in the act of appropriation constructively and with dignity, honor, knowledge, and respect for the cultural other that is informed by an awareness of the histories that have shaped the culture of the so-called other (Sharma 2010: 271). We see examples of this in White jazz musicians who contributed to the push for desegregation of clubs (Jones 1963; Sharma 2010: 264) or in White rappers who were socialized by the Black nationalist sensibilities of the crews they grew up listening to. Hinted at above, in contradistinction to the act of appropriation as a form of “othering” is that of “appropriation as identification” with the object of “othering” (Sharma 2010: 237). In this instance, appropriation signals solidarity with the cultural practices of the other rather than a colonizing co-optation of the other’s life-world—as we witness in Dolezal’s confused and delusional self-association with Blackness.

Seeing appropriation as a means of identification, however, first requires that we rearticulate the terms and politics of identity that police acts of appropriation. In so doing, we get out of thinking that appropriation only and ever equates to stealing or inauthentic borrowing (Sharma 2010).

For sure, the question of racial authenticity as it pertains to the issue of appropriation and the boundaries of cultural ownership is a tricky one to answer. Yet the fluidity of race as a concept calls us to find new ways to engage the tired politics of racial identity, challenging us to break ties with strict adherence to cultural mores around race and racial authenticity that ultimately prevent cross-racial fertilization (Sharma 2010). To sample hip hop studies scholar Nitasha Tamar Sharma: “When ‘culture’ is considered to be ‘owned’ by a demarcated group it is rendered static by trapping individuals within fabricated categories that reaffirm the logic of racism based on naturalized differences” (281).

The traditional script of racial identity politics relies on fixed, or essentialist, notions of race to say, for instance, that any non-Black performance of Blackness is racist and should therefore be dismissed as inauthentic. In recent scholarship on the matter, cultural theorists—riffing on the concept of racial formation (see, for example, Omi and Winant, Racial Formation in the United Sates 2014) which recognizes race as a social construct—encourage us to consider the ways in which appropriation does not necessarily equate to either fraudulence or inauthenticity; “theft” or “colonization” (Lott 1993, Lipsitz 1994; quoted in Sharma 2010: 264).

As Black sociologist John Jackson goes at length to discuss in his book Real Black: Adventures in Racial Sincerity (2005), racial authenticity claims, specifically in terms of Blackness, run the risk of “ossifying race into a simple subject-object equation, reducing people to little more than objects of racial discourse, characters in racial scripts, dismissing race as only and exclusively the primary cause of social domination and death” (15). In saying this, Jackson argues that sincerity should function as the real litmus test for cultural membership. A shift from an emphasis on racial authenticity to racial sincerity works to engage the interior motivations of those involved in acts of appropriation and gets us to consider the possibilities for coalition building through multiracial deployments of an anti-essentialist Blackness, in particular, and race, in general. In this way, race can function not as a cause for domination and death, but for mutual empowerment and life.

Again playing on Sharma, this shift in approach beckons us to interpret appropriation according to a comprehension of actors’ ideologies (238). Given the amorphous nature of race and the effortlessness with which we can find ourselves in the act of cultural borrowing, to the point of assuming a racial identity other than our own, it is crucial to interpret acts of appropriation through a contextual lens, as Sharma would have it, so as to “dislocate authenticity from the body” (Sharma 2010:272) and focus more on the issue of identification in terms of one’s approach to to Blackness, for instance, rather than on the Blackness of one’s identity (sampling Sharma 2010: 215).

This is to say that, following the dual lead of Jackson and Sharma, our understanding of appropriation must be informed by an awareness of the political, ethical, and moral commitments of those who appropriate rather than their bodily identity. In this way, non-Black actors can, as Jackson and Sharma suggest (see also Johnson, Appropriating Blackness: Performance and the Politics of Authenticity, 2003), identify with Blackness as an ideology and/or epistemology—that is, a way of knowing—and of being in the world that is tied to a conscious awareness of the history of racialized oppression against Black bodies as well as an intentional dialogue with the various Black cultural responses to said oppression that find expression in books, music, and political activism. In this way, appropriation can function as a form of flexible “identification” with the racial/cultural other.

“Appropriation as identification” in the meantime refuses to flatten racial difference—a flattening we see in the neo-liberal adherence to color-blind “multiculturalism” that actually diminishes the non-White other to the status of non-entity through its misguided celebration of sameness. We see a variation on this misguided discourse of “multiculturalism” in Dolezal’s claim to be Black inasmuch as she attempts to transcend the fact of her Whiteness by becoming Black. Her act of appropriation therefore falls short of identification in her own concern for assuming a Black identity that in fact reproduces the old script of racial politics which, unchecked, operates according to ossified articulations of race as bounded and secured. Indeed, Dolezal has locked herself into a Black identity in her act of racial crossing that, though she may believe signifies a gesture of identification, is an ironic repetition of a racial politics which says one has to be Black in essence in order to be Black in worldview–or taken further, one can assume a Black racial identity, dismissing the reality of difference, simply by adopting a Black worldview. This is not to get overly caught up in identity politics, which would be to fall into the very trap that scholars like Sharma warn us to avoid, but to reiterate the distinction between constructive and destructive forms of appropriation–a distinction that Dolezal ceases to make in act of over-identification.

Instead of either melting racial difference into a “post-racial” goop which implies a disregard for the atrocities that created racial difference in the first place or “ossifying” racial difference into a fixed dichotomy of “us” and “them” that shuts down the possibility for cross-racial exchange, “appropriation as identification” recognizes that there are specific histories to be accounted for in light of how the non-White other has been raced, or racialized, by Whites, at the same time that it seeks to create a dialogic of shared worldviews across the racial-cultural divide. This demands a practice of critical memory that resists the temptation to amnesia we see in gestures of multiculturalism; in those mistranslations of what it means to be transracial (echoing Lisa Marie Rollins; see “Transracial Lives Matter,” 2015); and in those acts of appropriation that co-opt the other’s identity wholesale while foregoing the possibility of dismantling one’s own Whiteness in self-critical rather than self-shaming ways (see “On Rachel Dolezal, White Privilege, and White Shame,” 2015). Ultimately, what “appropriation as identification” calls for is a critical recognition of difference at the same time that it invites us to intercultural and interracial bonding.

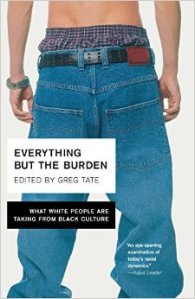

In the case of Ms. Dolezal, she had an opportunity to employ appropriation as a form of identification. However, she overstepped her bounds by going so far as to appropriate Blackness as an identity that she never had the rights to claim. In this way, she “othered” the very ones she sought to relinquish from the burden of “othering” and ultimately confused the political ideology of Blackness as her racial identity—taking up “everything but the burden” (Tate 2003) from those with whom she says she most identified internally.

In this, she unwittingly, or perhaps wittingly, leveraged her Whiteness to gain access to a commodified Blackness (hooks, “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance,” 1992; quoted in Collins, 2015) that resulted in an ultimately poor and insincere—which is to say, inauthentic—act of appropriation, discrediting all of her purportedly pro-Black advocacy and revealing a skewed racial logic that has subsumed her identification with Blackness into a Black identity itself.

To play on the insights of a colleague of mine who wrote some pithy responses to this incident on his facebook wall last week, Ms. Dolezal’s experimentation with her own Whiteness offers those of us who are White and who consider ourselves committed to the cause of decolonizing Whiteness, an invitation to become race traitors ourselves (thinking here of Noel Ignatiev’s “The Point is Not to Interpret Whiteness But to Abolish It,” 1997)—not in a way that would lead to an unwitting act of “appropriation as othering,” and therefore wrongful treason against our brothers and sisters of darker hue (à la Dolezal), but of “appropriation as identification” with those brothers and sisters and their plight as the objectified targets of racial terror. In this way, we can involve ourselves in the work of deconstructing Whiteness, committing an act of rightful treason against White Supremacy and the various and insidious manifestations of it both at the level of systems (the “macro”) and everyday interaction (the “micro”), so as to rearticulate it according to a discourse of anti-racism.

I believe Ms. Dolezal’s racial insincerity prods us to consider the fine line between Blackness as an epistemology and Blackness as a racial identity; between “appropriation as othering” and “appropriation as identification.” Insofar as she claims an investment in the ideology undergirding the Black freedom struggle—with Blackness as a political worldview informed, though not solely, by resistance to oppressive systems and structures that target racial minorities—yes, I agree with Abdul-Jabar, let her be “as Black as she wants to be.” However, insofar as she has never actually had to endure the heaviness of the historical burden that is racial Blackness by dint of her unexamined Whiteness, yet has proceeded to strip Blackness of its contextual content and meaning through identity theft and fraud, I say: “Step back, Rachel, and slow your roll.”