A version of this article was originally published in We Are Already One: Thomas Merton’s Message of Hope (2015) on Fons Vitae Press. Republished with permission.

We claim the present as the pre-sent, as the hereafter.

We are unraveling our navels so that we may ingest the sun.

We are not afraid of the darkness, we trust that the moon shall guide us.

We are determining the future at this very moment.

We now know that the heart is the philosophers’ stone.

Our music is our alchemy.Saul Williams, “Coded Language,” from Amethyst Rockstar (2001)

Though he has remained an ever vigilant presence in my life since I was first gifted Seven Storey Mountain by a close friend and mentor in the fall of 2001, my first semester of college at Philadelphia’s La Salle University, it’s been a few years since I’ve thought seriously about Merton—a man I consider, like so many other of his readers, to be a spiritual father.

This is ironic, in a way, because he led me through my undergraduate years as a student of religious studies, and continued to accompany me both personally and professionally through two masters programs—in English Literature at Arcadia University in Philadelphia and Systematic Theology at the Jesuit School of Theology at Santa Clara University (JST-SCU)—and a slew of Merton Society meetings. Indeed, I first came to Berkeley, California, my current place of residence, almost four years ago with the intent of making him the focus of a Ph.D. at the Graduate Theological Union (GTU), where I am currently engaged in doctoral work that has very little to do, at least ostensibly, with Merton.

Upon acceptance into the GTU’s common M.A. program in the spring of 2010, however, Merton was front and center.  Taking up work I had already started at Arcadia, I wanted to engage Merton as a mouthpiece for the politics of mysticism and its role in facilitating societal transformation. I had it in mind to further what scholars such as Lynn Szabo and Ross Labrie accomplished with their own detailed exploration of Merton’s mystical poetics and examine the ways in which Merton’s poetry has implications for a shift in social consciousness necessary to creating a more just society. Undergirding this claim is the still strong belief I have in the power of literature to influence human rights discourse and, as American political philosopher Martha Nussbaum posits in Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education (1999), nurture “powers of imagination that are essential to citizenship” (85).

Taking up work I had already started at Arcadia, I wanted to engage Merton as a mouthpiece for the politics of mysticism and its role in facilitating societal transformation. I had it in mind to further what scholars such as Lynn Szabo and Ross Labrie accomplished with their own detailed exploration of Merton’s mystical poetics and examine the ways in which Merton’s poetry has implications for a shift in social consciousness necessary to creating a more just society. Undergirding this claim is the still strong belief I have in the power of literature to influence human rights discourse and, as American political philosopher Martha Nussbaum posits in Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education (1999), nurture “powers of imagination that are essential to citizenship” (85).

For sure this is a tenet that Merton himself would hold true. Hence his prophetic “Message to Poets” and “Answers on Art and Freedom,” which close his prose-poetic magnum opus Raids on the Unspeakable (1966)–a text that became the centerpiece of my GTU master’s thesis. In it I interpret Raids as a political theology using work by Christopher Pramuk and Johann Baptist Metz to sharpen my hermeneutical lens. In returning to Raids, I find Merton there embodying perhaps more fully than any of his previous works the parrhesia (Greek for “free speech”) that he does so well to unpack in theoretical terms in The New Man (1961) and which Jonathan Montaldo treats deftly in his manuscript “To Uncage His Voice: Thomas Merton & Parrhesia [Free Speech].” Merton likens the concept—which refers traditionally to the “rights and privileges of a citizen in a Greek city state” to “speaking one’s own mind fully and frankly in the civil assemblies by which the state is governed”—to human intimacy with God “in work as well as in contemplation” (NM 72).

Merton meanwhile culls from the writings of the Church Fathers and his own allegorical reading of the Judeo-Christian creation myth to interpret parrhesia as the “symbolic expression” of the human person’s self-actualization in love (NM 74). This happens by way of laboring with “some consciousness of the value of human society” that puts us “in dialogue with reality” (NM 80)—a figurative “conversation with God” which Merton understands as the “free spiritual communion of being with Being” (NM 76) that duly manifests not only in the fact of being human, but in the intimacy of being-for-other (read: human relationship).

As an expression of parrhesia, Raids provided Merton the space to come most fully into himself as activist, artist, global citizen, monk, poet, and theologian who tears the fabric of social orthodoxies through the power of “free speech” in order to do his part, as Martin Luther King, Jr. said of his own work, in ridding the world of social evil and thereby come into deeper intimacy with God. This is no small task to say the least. And it is one that Merton challenges his readership to take up in Raids when he urges us to dispel the magic of political propaganda through love (caritas)—giving witness through his own “free speech” to an underlying eschatological faith-hope in the possibility of “the word” to usher in a new dawn of fidelity to life in “the Spirit” rather than to artificial systems; to human solidarity rather than to the mere collectivity of the herd (as illustrated by Eugene Ionesco’s metaphor of “rhinoceritis” which Merton expounds in “Rain and the Rhinoceros”; see also RU 156-57).

That being said, I closed Raids with the completion of my master’s thesis and the prospects of doctoral work at the GTU looming on the horizon in the spring of 2012, wondering: Where do I go from here? What more, if anything at all, do I want to write about Merton? What do I do with the work he has left me to take up?

Feeling as though I had exhausted my stint with Merton, I have to admit that by the time I submitted a second thesis on him, I was itching to explore new terrain; to bid happy farewell to the figurative parent who reared me intellectually in/on the mystery of parrhesia and find my own voice as the would-be poet to whom Merton addressed his penultimate essay of Raids. This led me to ask the further question about what most enlivens me, about what makes me feel most fully myself (and therefore a poet as Merton would have it), particularly in terms of continuing the academic route on which I was set.

Like Fr. Louie playing bongos inside of his Gethsemani hermitage, photographed in the iconic black and white picture taken by Ralph Eugene Meatyard in 1968, I found myself drawn to the sound of the drums, specifically as elicited in the work of my favorite rap artists. Along with Merton’s catalog, it was hip-hop that kept me in step to the rhythms of life through my formative years—which included an undergrad and two grad programs dedicated to the mystic’s teachings. When finally it came time for me to solidify a set of research questions that would take me through yet another degree, I turned my attention away from Merton’s poetry and toward the poetics and politics of rap music.

Indeed, before Merton even entered my world, hip-hop taught me what it means to really “dance in the water of life” as when I was nine years old and first heard the jazzy interplay of sampled vibraphones, bass, and drum on A Tribe Called Quest’s “Award Tour” bumping out of my stereo, tuned to the frequency of Baltimore’s rap radio station 92 Q. It was then that I first learned, at least unconsciously at that point, what parrhesia is all about.

Yet it is with the image of Merton on the bongos in mind that I presently engage what I call, riffing on American jazz drummer Max Roach, the “politics in the drums” which lies at the heart of a now global cultural phenomenon that post-colonial theorist George Lipsitz, appropriating the terminology of humanist intellectual Antonio Gramsci, coins a counter-hegemonic “war of position” (see Lipsitz, “Diasporic Noise: History, Hip Hop, and the Post-Colonial Politics of Sound” in Dangerous Crossroads: Popular Music, Postmodernism and the Poetics of Place, 27, 38). Deeply informed by Merton’s self-identification as poet on the margins—clapping stretched canvas in happy protest of the “hegemonies that be” or listening to jazz and blues records as they spun on the turntable situated in the cosmopolitan space of his hermitage—I have found in rap music a medium of and variation on parrhesia that has allowed society’s most disenfranchised to take ownership over their own lives, as well as the means of production, through the power of the word—what in West African parlance is called Nommo.

Yet it is with the image of Merton on the bongos in mind that I presently engage what I call, riffing on American jazz drummer Max Roach, the “politics in the drums” which lies at the heart of a now global cultural phenomenon that post-colonial theorist George Lipsitz, appropriating the terminology of humanist intellectual Antonio Gramsci, coins a counter-hegemonic “war of position” (see Lipsitz, “Diasporic Noise: History, Hip Hop, and the Post-Colonial Politics of Sound” in Dangerous Crossroads: Popular Music, Postmodernism and the Poetics of Place, 27, 38). Deeply informed by Merton’s self-identification as poet on the margins—clapping stretched canvas in happy protest of the “hegemonies that be” or listening to jazz and blues records as they spun on the turntable situated in the cosmopolitan space of his hermitage—I have found in rap music a medium of and variation on parrhesia that has allowed society’s most disenfranchised to take ownership over their own lives, as well as the means of production, through the power of the word—what in West African parlance is called Nommo.

In this, Merton has provided the inspiration, the necessary push, for me to enter the dance of parrhesia as it takes place in hip-hop culture as well as my work as a student of the rap academy, rife with street-level philosophers whose gift of “free speech” signifies the “combined functions of hermit, pilgrim, prophet, priest, shaman, sorcerer, soothsayer, alchemist and bonz” (RU 173). By entering into conversation with these figurative high priests of rap-inflected parrhesia as (ra)parrhesia—including the likes of Nas, Jay-Z, 2Pac, Kanye West, Kendrick Lamar, Killer Mike, Shabazz Palaces, Ab-Soul, Erykah Badu, Lauryn Hill, Talib Kweli, Mos Def, Project Blowed, among many others—I enter into deeper intimacy with God, embodying my own capacity for “free speech” in the process of interpreting for and with others the insights gleaned from what a former GTU professor of mine calls “message music.” Insights that reveal a deeply invested commitment, riffing on Merton, to the pursuit of political solutions to problems “that endanger the freedom of man [sic]” (RU 171)—not least of which is institutionalized racism as it operates in a global capitalist economy that, in the post-industrial predicament of American cities, has blighted once prosperous North American urbanscapes populated mostly by racial/ethnic minorities.

Inasmuch as my current academic pursuit entails an examination of the ways in which black cultural production in the form and content of rap music (read: [ra]parrhesia) fosters new ways of being in and for the world that are deconstructive of the white supremacist status quo, I am being challenged to keep in check the egoism of the “false self” by which I have been conditioned in a socio-economic milieu that privileges both my whiteness and my maleness. Positioned in many ways as the well-meaning “white liberal” to whom Merton addresses his searing essay on American race-relations in Seeds of Destruction (1964), my work implicates me in a practice of self-reflexivity that is an act of intersubjective parrhesia in its own right.

It invites me, echoing James Baldwin in The Fire Next Time (1963), to “fruitful communion with the depths of my own being” that serves to decenter my subjectivity (and the assumptions that inform it) in encounter with the so-called “other” (130 ff) and there root out what Merton calls in Seeds of Destruction the “cancer of injustice and hate which is eating white society and is only partly manifested in racial segregation with all its consequences” (SD 45-46). Such an act of “free speech” is grounded in the purpose of fulfilling the democratic promise upon which the American project is founded, a mission Merton himself worked to accomplish during his own lifetime as a prophet of parrhesia.

Rap music—as a cultural platform for minority youth in particular and young people in general to embody the freedom of self-expression—is in its own way empowering me to answer Merton’s injunction in Seeds of Destruction to “think black” (60); that is, to reorient my understanding of the world by adopting an epistemology informed by the plight of those who suffer the injustices of systemic racism. In this performative dialogic, this dance of “free speech,” between me and the racialized other, I am called to further engage the “crisis in which we find ourselves” (SD 60) as a society still deeply entrenched in what black feminist bell hooks calls the “imperialism of patriarchy” (see bell hooks, Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism, 1999).

Furthermore, it is cluing me into the “streets” and the “ghettoes” where, as Merton notes in Learning to Love (1967), “much of the real germinating action in the world, the real leavening” lies (231). In this, I am being summoned (along with rap’s actual practitioners and other like-minded “hip-hop heads”—be they black, brown, white, red or yellow–to plumb the depths of my own unique possibilities for civic engagement and thereby conduct a Mertonian “raid on the Unspeakable,” implicating rap music, and my love for it, in what black cultural critic Huey Copeland calls, à la the intellectual contributions of black literary theorist Saidiya Hartman, a “rhetoric of redress” aimed at reparative justice (See Huey Copeland, “Fred Wilson and the Rhetoric of Redress” in Bound to Appear: Art, Slavery, and the Site of Blackness in Multicultural America, 2013).

So it is to the imagined boom-bap of Merton’s playful bongo beats that I march into the matrix of cultural production that black public figures from Afrika Bambaataa, Queen Latifah, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five to Tupac Shakur and his protégé Kendrick Lamar have helped shape, remapping the global landscape into a social sphere more livable through electronically-based, rhymed storytelling that functions to develop the essential moral capacities, recalling Nussbaum’s insight into narrative, necessary for a kind of (ra)parousia to occur—understood in the context of American race relations as the realization of the Ellisonian dream of democracy that the Harlem Renaissance-era author espouses in his seminal The Invisible Man.

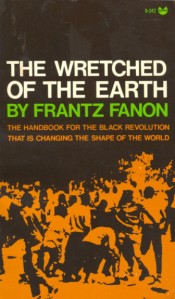

Signifying on traditional conceptions of what constitutes literacy so as to create an entirely new lexicon that is at once  textual, verbal and non-verbal, rap music acts as kind of “Talking Book,” to borrow a trope from black literary theorist Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism, 1988), which provides its practitioners, particularly those in ghettoized or under-represented communities where the “real leavening” takes place, a means of enunciating a specific stance, location and visibility within a broader cultural framework that has historically reduced them to the status of the invisible or, in Frantz Fanon’s terms, “the wretched of the earth.”

textual, verbal and non-verbal, rap music acts as kind of “Talking Book,” to borrow a trope from black literary theorist Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism, 1988), which provides its practitioners, particularly those in ghettoized or under-represented communities where the “real leavening” takes place, a means of enunciating a specific stance, location and visibility within a broader cultural framework that has historically reduced them to the status of the invisible or, in Frantz Fanon’s terms, “the wretched of the earth.”

In the same way learning to read and write allowed slaves a means to contest their oppression and use the master’s tools of literacy to speak themselves into subjecthood, rap music’s Nommo, as an African-derived variation on parrhesia, empowers its practitioners (and its audience) to disarticulate, or dissemble, the oppressive historical circumstances in which they find themselves, and rearticulate their discursive terrain in a speech act of forthright self-assertion. As such, rap music offers the necessary resources for a subtextual analysis of history, on the part of artist and audience, which discloses unpopular political truths pertaining to systemic evils such as racism and, as black critical theorist Houston Baker Jr. argues in terms of the blues, serves to reorient historical discourse from the perspective of the oppressed (see Houston Baker, Jr., Blues, Ideology and Afro American Literature: A Vernacular Theory, 1984).

Rap is in this way an exercise in an expansive kind of literacy which challenges us, as did Merton’s mystical poetics, to re-conceptualize language as more than the mere manipulation of words. Put another way, it pushes us to take language, and the way we use it, more seriously. As with Merton’s “Message to Poets,” rap’s underlying ethos invites us to see language as an embodied act of self-fashioning that takes on many forms, styles, and articulations, and has everything to do with keeping in step to the soul’s beat—that embodied metronome of rhythm and rhyme which empowers its speakers to “claim the present as the pre-sent” and, in an eschatological turn, determine the future “at this very moment.” In this same way it gestures toward the love and hope that undergirds a sturdy “politics of conversion”—what in Race Matters (1994) black cultural critic Cornel West deems the antidote to the problem of “spiritual impoverishment” in America.

That said, I’m grateful to Merton for awakening me to the narrative play that is inherent in the gift of “free speech,” as intimate conversation with God, and the many ways it manifests through different forms of poetry—be it the anti-poetics of the Trappist monk’s later prose poems that constitute Raids; the politically polemic poetics of such Golden Era rap classics as Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold us Back (1988); or, with Sophia’s blessing, my own work as an aspiring hip-hop scholar. And I’m also grateful for the opportunity and space this essay has given me to enter into a figurative “cipher” with someone whom I consider a dear father, brother, and friend in Sophia. [A “cipher” is a situation in which two or more rappers form a circle and play off of each other in an informal performance of freestyle, or improvisational rapping/talking.]

Hers is a wisdom that Merton would find resonant in rap’s vernacular Nommo, resplendent with a message of hope for our time in its function as a kind of “free speech,” a (ra)parrhesia, imbued with potential for bringing us into deeper intimacy with God, as if in cipher, through deeper intimacy with each other and ourselves. An intimacy which, thinking of Merton in (ra)parlay with Baldwin, takes us beyond words and into a kind of “wordless communion.”

I have no doubt that were Merton still alive at the time of hip-hop’s burgeoning, and even still today as the genre continually evolves into new forms and patterns of “free speech,” he would be tuned in to the sonic frequency which is rap, “routed” in the Afrodiasporic politics of the break beat—what spoken word poet and rapper Saul Williams allegorizes in his invective, “Coded Language,” quoted in the epigraph, as the “missing link connecting the diasporic community to its drum woven past.” Indeed, I can hear Merton right now, in the spirit of (ra)parrhesia, chanting with fellow anti-poet Williams: “Motherfuckers better realize! / Now is the time to self-actualize!”

Reblogged this on CONTACT.

LikeLike

Thank you for the nod, worldhypetv!

LikeLike